“If you tell me I can’t work, I can’t feed myself.

“If you have experience and capability and then they find out you’ve been in prison, suddenly they are not hiring,” she said. After several years in prison, she was released in 2008. Marie Jones, 47, who lives near Savannah, was sexually abused when she was young, had her first child at age 12 and repeatedly ran afoul of the law. Yet many formerly incarcerated people who do work barely scrape by, Landers said. That’s why classes in coding are a great investment, said Julie Landers, program manager for Persevere, a national nonprofit group that works with current and formerly incarcerated people.įor incarcerated people nearing release, Persevere runs coding classes - six hours a day, five days a week - like the course Drequan Walker took. Society has an interest in keeping people with criminal records in good-paying legal employment, he said. It’s costly to chase down and prosecute lawbreakers and it’s very expensive to pay for incarceration. “There’s such an upside, there’s a business case for second-chance hiring.” “It isn’t just a charity case - it makes good business sense,” said Wade Askew, policy manager of the Georgia Justice Project. Gluing that coalition together is a mix of idealism, generosity and purely financial incentives. Burt Jones, business groups like the Metro Atlanta Chamber and the Georgia Justice Project, a non-profit group that works to reduce barriers for incarcerated people re-entering the workforce. The bill never got to a vote, but it will be presented again next year, he said.īackers of the measure include Republican Lt.

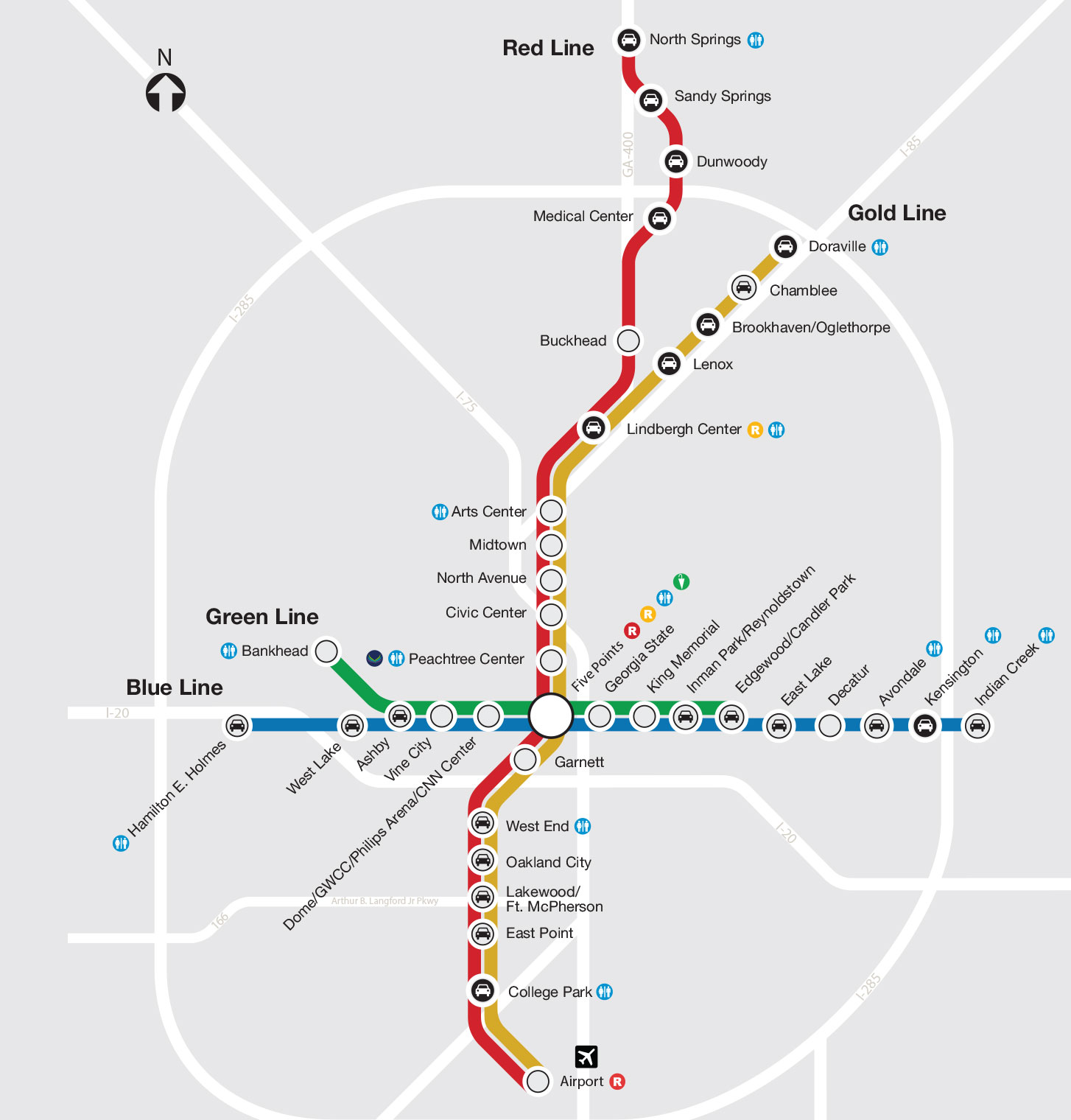

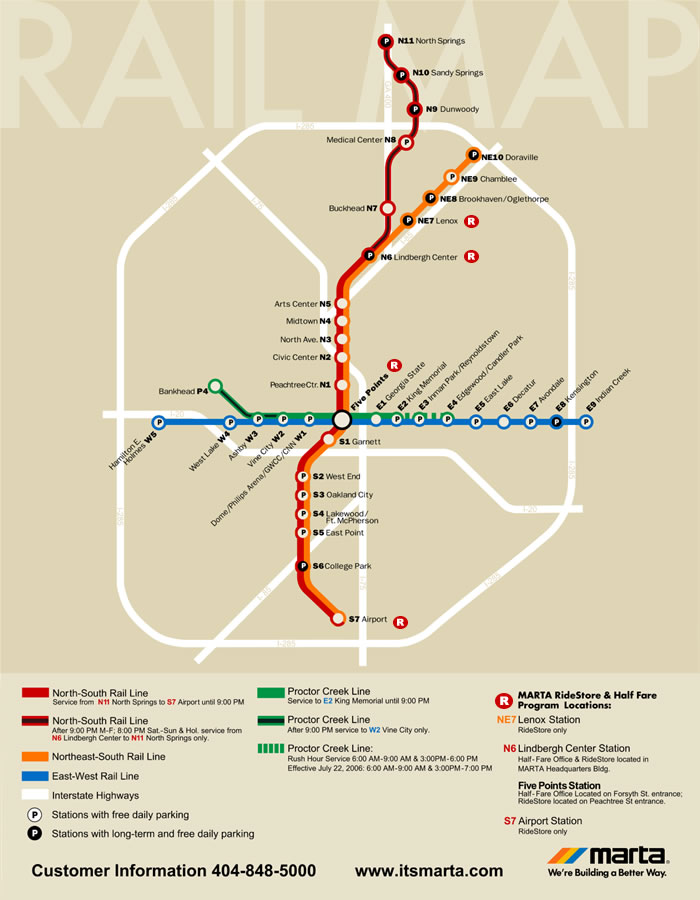

ATL MARTA JOBS LICENSE

His bill would keep boards from rejecting a license unless the person posed a substantial safety risk. Brian Strickland (R–McDonough), who sponsored a bill in the recent legislative session that would have limited that authority. Georgia law permits licensing boards to deny an applicant without explanation, according to state Sen. Some advocates are pushing for “clean slate” initiatives that would seal many criminal records, effectively eliminating the issue during job applications.Īnother hurdle is certification, which is needed for nearly one-third of lower-wage jobs in Georgia, including barber, manicurist, fire alarm installer, veterinarian technician and athletic trainer, according to a study by the Georgia Public Policy Foundation. With unemployment low, many companies have complained that they have trouble finding workers, especially for lower-paying jobs. ‘Clean slate’Įconomics has been pushing employers toward a more accepting stance. McBroom’s father was incarcerated for much of his son’s adolescence, but the son stayed straight and became a success. “As somebody who’s been blessed, it’s my responsibility to give back to my community.” Hiring people who have left prison is also the right thing to do, he said.

So some companies that do “second-chance” hiring are reluctant to acknowledge it publicly.īut maybe the risk in hiring people who have been in prison isn’t much different than the gamble on any other new hire, said Antonio McBroom, co-owner of 14 Ben & Jerry’s ice cream outlets, including stores in Atlanta and Athens. But there’s also concern that customers will be nervous about a person with a criminal record serving them. Many employers worry about a hire going wrong. Within five years, more than half of those will be arrested again. Nationally, more than 600,000 people are released from prisons and jails annually, including about 17,200 in Georgia, according to Prison Policy Initiative, a 22-year-old Massachusetts think tank that researches criminal justice issues. Georgia’s 34 state prisons hold about 47,000 people, while nearly as many are in local jails, according to the Georgia Department of Corrections. It’s about assuring them that I am going to be the person that they want me to be.”įor people who have been incarcerated, the unemployment rate is about 25%, or five times higher than the national average, according to the Prison Policy Initiative. I knew the kind of life I wanted to have. “I understand that I need to show that people can trust me,” he said.

“They never said the reason they don’t want to hire me, but maybe it’s my background,” Walker said.Ī background that includes spending five of his 22 years behind bars for robbery.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)